Donkey Kong Bananza - Game Design in Excess

How Nintendo makes game design play second banana to player agency

17/08/2025

Warning - this article contains spoilers for Donkey Kong Bananza. I won’t touch on actual plot spoilers, but I will touch on the powers DK gains, and level design - including late-game challenges. I also discuss the game design of Super Mario Odyssey, The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, Animal Crossing: New Horizons, and Pikmin 4, although again with no spoilers. (Not sure how you could spoil Animal Crossing though).

Donkey Kong Bananza is a truly fascinating game. It represents a pinnacle in Nintendo’s design philosophy for the Switch era - and how player agency has become so far at the forefront of their design philosophy that it starts to eat away at its own design. The game's mechanics have become bigger than themselves - and I think the reaction to this game on a universal front has been super interesting, and really shows how game design ideologies on a market-wide front have adapted and grown over time.

I’d like to preface this by saying that… I am simultaneously a huge fan of this game, and find that at times I am not a fan at all. Games criticism can very much boil down to “this game is amazing” or “this game is terrible” - opinions need to be extreme, everything is the best thing ever, or the worst thing ever - because eyes need to be grabbed. So I want to say that upfront. I am not going to hold back on my criticisms of this game - but that does not mean I didn’t like the game. Those criticisms will likely speak much louder to an internet enamoured with this game - but I find the way that this game develops as you play it to be fascinating, and even if I ended up feeling more critical of it by the end; that doesn’t mean that it’s bad, or that you shouldn’t like it. For a game daring to blast through the bland everyday; it has my utmost respect.

DK Bananza takes a classic collect-a-thon 3D platformer, and asks “what if everything could be destroyed?” The game is heavily built around its terrain destruction mechanic, and largely sets platforming challenges to the wayside. As DK traverses the underground, the game feels a lot more built around exploring these areas, climbing, finding bananas and fossils - rather than platforming through specific set pieces.

This game's predecessor, Super Mario Odyssey - is much the same. Wide open spaces, moons scattered everywhere, challenges both unique and replicated in each world, and little side pockets of more dedicated pockets of challenge. Both games feel incredibly focused on the “collecting” part of being a collect-a-thon. In Mario Odyssey, there were quite a few locations where you could make use of your moveset to tackle challenges in different ways - there’s a large amount of player expression at your disposal, and you have a vast toolbox to tackle any challenge at hand. Do you take the simple root the game presents to you - using the captured enemies as they are intended? Or do you pull off some sick-ass movement tech with Mario? Backflipping, long jumping, cap diving to your destination in style. That amount of player agency is very much Odyssey’s thing.

Bananza feels like the next evolution of that idea - there is impeccable movement tech you can pull off: the spin jump, chunk jump, roll, dive, it’s all fabulous! But you can also destroy almost all the terrain, you can climb almost any surface! Any challenge can be tackled hundreds of ways. Banana underground? You could follow a little platforming challenge to get there, or you could dig around and find it from the other side from your exploring!

It feels like the intention with this was to equally reward the “explorative” player, the one that makes the best use of the climbing and digging - and the “skillful” player, the one that masters DK’s moveset and leaps and bounds everywhere. And for the first half of this game - I fell for this design ideology hard. DK’s starting moveset gives the player an excellent amount of leeway in how they tackle challenges - the intended route is clear, and you don’t have all of the tools to completely skip it, but you have the tools to carve your own path.

Digging in this game is initially super tactile and empowering. Different terrain has different properties and strength, and you can throw and crash and smash through the earth in a multitude of different ways. Accidentally skipping a cool platforming challenge to grab a banana in an unintentional way feels like a bold game design decision! It felt fun and exciting.

But over time, it became clear that these two ideologies, “explorative” play and “skillful” play, are not balanced at all. 90% of challenges are better to be tackled by going around the problem with your exploratory moveset, rather than making use of your own player skill. And unfortunately, it’s the less-fun part of the moveset that’s much more powerful.

THE BANANZA DILLEMA

This problem expands tenfold once the Bananza powers come into play. DK obtains 5 incredibly powerful forms throughout the game, that he can transform into at will as long as his Bananergy (great name) meter is full. This meter is almost always full, and using any Bananza power will usually result in obtaining enough Gold to use it again - so this limit basically doesn’t exist[1]. All of these powers are interesting to discuss here!

The Kong Bananza is the first you obtain - and is by far the most straightforward and balanced. You punch faster and stronger, and can naturally break stronger materials like concrete. It feels great to crack this open in combat, or for exploring - but it merely adds a bit of “oomph!” to those interactions, rather than trivialising them altogether…. Kinda? Combat in this game is already pretty trivial, so Kong Bananza doesn’t exactly help that - which would be fine, but it seems like they wanted combat to be somewhat of a focus given the many side-rooms dedicated to combat encounters, and the myriad of bosses, and the upgradeable health bar. (In the grand scheme of issues I have with this game though, this is pretty minor).

Zebra Bananza allows the player to run very fast - which is mostly used as a key in its respective world - the Freezer Layer. Outside of that world, you very rarely need it - and you technically don’t need it at all if you pull off a tricky sequence break. After playing this layer - this is kind of what I assumed each Bananza would be like. A utility upgrade with a context sensitive puzzle it can solve.

Oh, how wrong I was.

The final 3 Bananza - Ostrich, Elephant and Snake - get to the point of completely trivialising nearly every single interaction in the game. Ostrich can float and then glide, and Snake gives the player two huge jumps. These two have insane synergy with each other: you can use them in combination to jump over every late-game platforming challenge. Zero exaggeration on that every. So much of the game feels like it wasn’t designed with these abilities in mind - which is just insane to me?

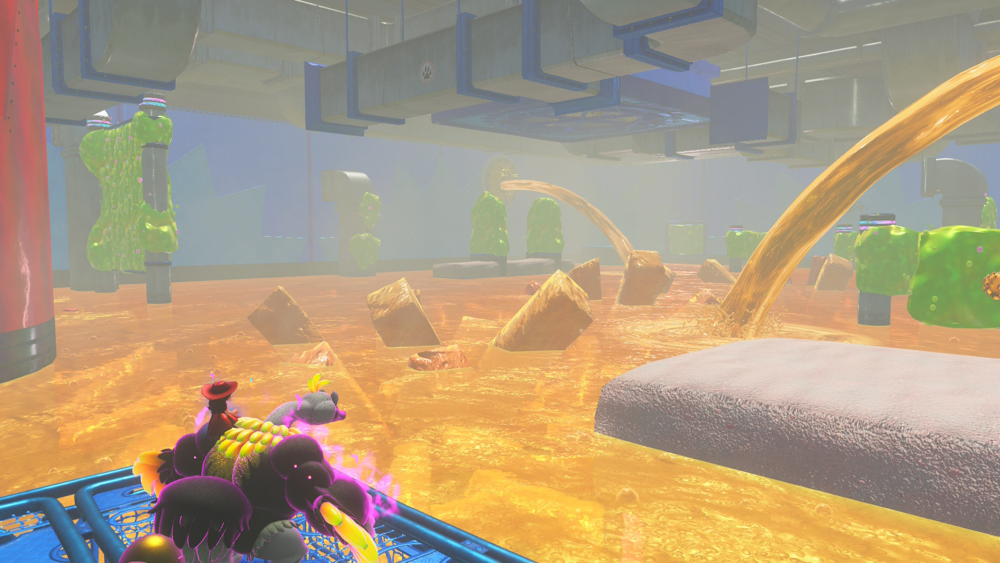

An example is this room of burning oil in the Feast Layer - you are supposed to ride around on these salty platforms, avoiding obstacles to get through… oh? You can just jump with Snake and fly with Ostrich to the end? And it’s much easier?

Even in the final, endgame platforming challenge - this game's equivalent to Champion’s Road or Grandmaster Galaxy - you can skip multiple sections with the Snake-Ostrich combo.

Usually when I talk to people about this - I get given the response of “oh, you don’t have to use them!” But like… this, to me, feels like a cop-out. You can add overpowered abilities to your game and make them fun! And frequently, when playing Bananza, I was reminded of a different game series that does this very well. And, shockingly, it’s Sonic.

Throughout classic Sonic games, you can find hidden Special Stages in the main levels to collect Chaos Emeralds; and upon collecting all seven - you can transform into Super Sonic. This already takes a good chunk of the game unless you are specifically hunting down the Special Stages as optimally as you can, which is tough to do when first playing. Then, in each level, if you collect 50 rings: you can transform into Super Sonic - which makes you incredibly fast, practically invincible, and overwhelmingly powerful - at the cost of slowly losing said rings you collected. Once the rings hit zero - you lose your Super form and are left vulnerable (as having zero rings in Sonic basically means you are one hit away from death).

Super Sonic is a fantastic mechanic for this kind of game - it heavily rewards mastery in multiple facets - getting good at the Special Stages, keeping your rings, learning the level design. It makes you feel awesome! And I think Bananza could have learned a bit from this.

Going Bananza in DK doesn’t feel rewarding - you have access to your more powerful form 99% of the time. It doesn’t reward understanding the level design - it rewards skipping the level design. There is no risk-reward, there is no penalty, it is always the best option.

It feels like Nintendo’s idea was to create a playground - providing you with a tonne of tools, and allowing the player to figure out which tool is best for which scenario, and play how they want to! …In reality, it feels like a shape-sorter toy - where every shape is incorrectly sized and all of them can fit into the square hole. Every problem can be solved with the Snake-Ostrich combo - and doing so takes no skill to do so.

The other side of this is the Elephant Bananza, which sucks up terrain with insane force, range and speed. This one feels most like direct power-creep of the Kong Bananza - trading that satisfying, tactile “oomph!” of punching everything for ultra-efficient suckage that destroys terrain so instantly. The game constantly rewards you for just sucking everything up - you’ll find hidden bananas, fossils, gold, items, and maps - which lead to more fossils and bananas. And since you can always just suck up more gold - it makes the game’s shop system, and that awesome feeling of exploration that the first half of the game actually nailed, feel trivial in itself.

The game gave me so many good tools to tackle each problem - that suddenly each individual problem felt trivial, and the game switched from feeling awesome… to feeling tedious, and really overstaying its welcome. Which sucks - because I actually loved this game before that.

Everything before and including the layer where you got the Ostrich Bananza felt amazing! The movement was awesome, the exploration was awesome - and the ability to sequence-break felt really novel. It felt like a bold new thing - Nintendo giving the agency to the player so they could tackle it their own way. Even just writing this, I’ve been listening to the Lagoon Layer music and feeling weirdly nostalgic for how promising it was at the start! And seeing how those sequence breaks have been employed by the community to skip major sections, and pretty much every Bananza power - it’s so cool! This game is a speedrunner’s dream, and pushing the game to its absolute limit is amazingly satisfying.

It’s a bit of a self-fulfilling prophecy, too. I feel like if I hadn’t been going out of my way to get every banana and fossil - I wouldn’t have burnt out on it so strongly. I think I was just having so much fun collecting everything in that first 50-60% of the game, that I assumed that momentum would carry through. But since the game seemed to keep going on and on, and said late-game parts were getting easier and easier - the entire thing was starting to feel more pointless by the end[2].

The issue I had is that the world of awesome game design and the world of player agency collided too soon. It felt like before I was done with the game’s initial magic, I had outgrown it. It doesn’t give any space to nourish your skillset - I did all of the hardest endgame content, and I never felt like I mastered the game, because I never felt like I had to. And that therein lies how I feel about Nintendo’s modern design philosophy.

A SWITCH IN GAME DESIGN PHILOSOPHIES

I already touched on Mario Odyssey - but the game that really started this idea was The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild. An absolute feast of a game that combines modern day open world with classic Zelda, and hints of immersive sim. I remember playing Breath of the Wild and being completely astounded by how intricate its systems, physics and puzzle design was. It has very consistent rules - metal always conducts electricity, setting fire to grass always creates an updraft; and gives the player the agency to how they solve the puzzles. Classic Zelda was usually very very strict about that - use item X in dungeon Y to solve Z. Breath of the Wild, on the other hand, feels like a game of madlibs - the fun of the game comes from coming up with your best, or craziest, solution to any problem.

Both Mario Odyssey and Breath of the Wild came out in 2017 - and their near universal acclaim seems to have caused Nintendo to lean heavy into this “improv” style of game design. The “yes, and”, the playground where anything could happen, where you have all of the tools at your disposal. And at first - this was mindblowing! Both of the aforementioned games felt like complete masterpieces to me when I first played them.

The issues that I have with this design ideology first crept up with the release of Animal Crossing: New Horizons. After adoring New Leaf on the 3DS - I was so excited for a new game! Animal Crossing, to me, has always felt like a living, breathing piece of art. Everything is personalised. Whilst characters had tropes they would follow - they had huge amounts of depth and would remember so much! They would get mad at you, they would move out on their own volition - they felt like they had agency. And your town would evolve in front of your own eyes! The game would track so many little counters and stats - you’d constantly unlock new little subtle things to keep you playing each day. Your high street would grow - it really captured this feeling of humble beginnings to becoming a nostalgic, grand place.

New Horizons doesn’t really do that. Your island doesn’t really change - it can change, but only by your design. Your villagers can move in and out - but only if you want them to. It felt like the game gave you all of the keys to the kingdom, and after a while, I just decided to lock myself out, because the intrigue wasn’t there. I wasn’t excited to see how things would change every day - because… they didn’t! Unless I wanted them to.

Pikmin 4 was one of my most anticipated game releases ever. Pikmin 3 felt like an amazing direction for the series - expanding and really refining the identity of the series into this real time strategy puzzle adventure. There’s nothing really like Pikmin - and on the lead up to Pikmin 4 - they coined this new term, “dandori[3]”, to describe the gameplay style of Pikmin, and being as efficient as possible. That felt like such a good step to getting the world to get Pikmin!

But Pikmin 4, similarly, felt like it traded that really unique, one-of-a-kind design philosophy that the Pikmin series had since the start for a design leading so much into player agency and design conveniences. There’s no penalty to going slowly - so there’s no incentive to be optimal. You have access to every type of Pikmin - but you can only bring 3 types of Pikmin into each area, and it recommends you the best types for each area, trivialising any element of strategy with your Pikmin loadout. If the game gives you the answer to a question before the question… Why should you think about a different answer to the question?

This is most emblematic with the existence of Oatchi - an adorable space doggy that trivialises almost every interaction in the game. Oatchi has the strength of 100 Pikmin, and is by far your best asset in combat. There is no problem in this game that an Oatchi-sized block cannot be shoved through… sound familiar?

I think this is so weird for me because… this is so unlike what I think of when I think about Nintendo. Their games, to me, have always felt tight and self-contained, about systems that are simple and easy to understand; but have a ceiling for mastery that is tested. And sure, that’s done more coherently in games like Pikmin than it is in Animal Crossing - but both are emblematic of this change.

All of these are games that thrive in excess - giving the player the most control, agency, the most bang for their buck. And for some people - this is the dream. Clearly, this style of design works for Nintendo. All of these games sold amazingly, and are beloved worldwide.

To me, Bananza just felt like the apex of this idea. It’s a ridiculously fitting title - it’s a literal bonanza, a smorgasbord, if you will! It is excess incarnate. It is an entire banana burger, it is a 1kg of gummy worms in game form. The first bite tastes so good. You want to eat more and more - but you get sick to your stomach. But you also have sunk cost fallacy, so you keep eating more and more until you can’t handle it any more… and the metaphor gets away from you.

Maybe it’s selfish and nonsense to take a good, masterfully crafted game - and ask for less. Less cool powers, less content, less freedom. But to me - game design has always felt like an art form of less-is-more. Giving players crumbs until they’ve eventually nibbled away at the whole loaf, and leave satisfied. If you give players the whole loaf to begin with - some will be thrilled, and others will be too greedy. Some players will take an inch, some will take a mile. For some players, game design in excess is a tiny, insignificant hurdle - but for me it became an insurmountable wall.

Maybe the only wall in the game that you couldn’t just jump over with a Snake-Ostrich combo. Heh.

<

[1] You can also instantly activate your Bananza with a Melon Juice. This came in handy… single digit times during my entire playthrough? You just always have full Bananergy when you need it.

[2] I will say that the actual final level rocks! Even my cynical mindset was able to broken by that sequence, even just for a little bit.

[3] I mean, technically it’s a japanese word that they started using in English to describe the gameplay style of the series, but I digress.